The Academy’s Public lecture series includes events named in honour of former Academy Presidents held across Australia.

- All

- 2025

- 2024

- 2020

- Cunningham Lectures

- Fay Gale Lectures

- Keith Hancock Lectures

- Paul Bourke Lectures

- Peter Karmel Forum

2024 Cunningham Lecture: Presented by Professor Betsey Stevenson Marriage, family and work in an age of rising gender equality Date: Thursday 11 April Time: 5.00 – 6.00pm lecture, 6.00 – 7.00pm […]

2023 Cunningham Lecture | Distinguished Professor Susan Danby FASSA Risks and opportunities: Building social contexts for young children’s digital interactions Exploring the complex intersection between young children and digital technologies […]

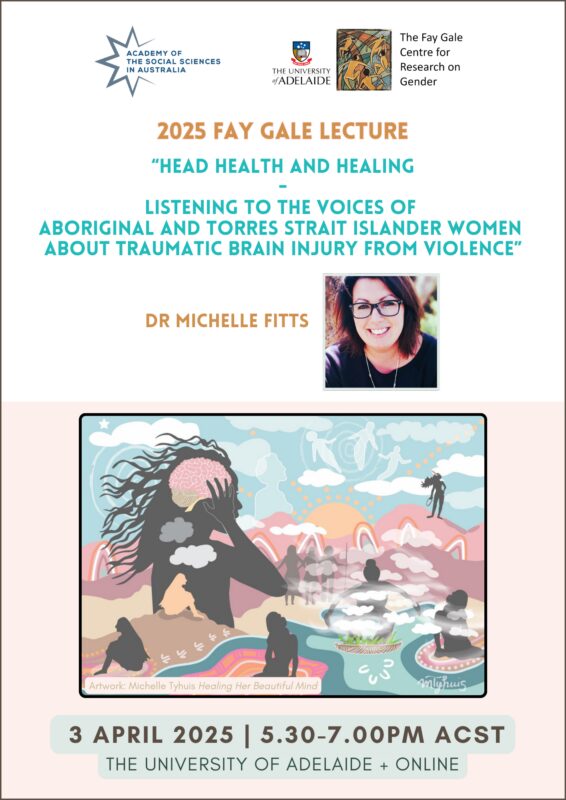

2025 Fay Gale Lecture: Presented by Dr Michelle Fitts ‘Head Health and Healing – Listening to the voices of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women about traumatic brain injury from […]

CEDA in partnership with the Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia, is pleased to invite you to participate in a discussion on tax reform with leading commentators. Tax reform […]

Indigenous language landscapes. Why a fuller understanding of Indigenous peoples’ language contexts is important 2024 Paul Bourke Award Lecture | Dr Denise Angelo with Indigenous language researchers: Tara Bonney, Marmingee […]

As we count down to COP29 in Azerbaijan in November 2024, global policymakers are dubbing it the ‘finance COP’. Funding climate action, domestically and internationally, is one of the critical […]

Using social science to inform hepatitis C elimination efforts in prisons 2024 Paul Bourke Award Lecture given by Dr Lise Lafferty. In this address Dr Lafferty reflected on a decade of […]

2024 Fay Gale Lecture: Presented by Professor Pam Nilan ‘Youth, Masculinity and the Far Right in Australia’ This lecture considered the nexus of youthful masculinity and far right discourse in […]

Keith Hancock Lecture 2023: Presented by Emeritus Professor Alison Booth Gender Gaps: Causes and Origins Recent research in experimental and behavioural economics has focused on the role that preferences might […]

2023 Fay Gale Lecture: Presented by Professor Cordelia Fine Battle of the Sex Differences: Where to begin? Date: Friday 25 August Time: 5.30 – 7.00pm AEST Location: Ingkarni Wardli, The […]

Unravelling the Thrills and Trials of Mixed Feelings in Consumer Behaviour Dr Felix Septianto 2023 Paul Bourke Lecture Positive emotions can inspire people to take action. But life can be […]

Climate finance: taking a position on climate futures Dr Sophie Webber 2023 Paul Bourke Award Lecture Date: Tuesday 5 September 2023 Time: 6pm – 8pm Venue: The University of Sydney

This special event featured the Paul Bourke Award Winner for Early Career Research, Dr Harry Hobbs as he explored modern treaty-making between Indigenous peoples and governments in Australia. This event […]

It’s Time for Change – New Perspectives on Body Image Associate Professor Gemma Sharp 2023 Paul Bourke Lecture About the Lecture Body image concerns are unfortunately very common. More than […]

To celebrate Laura Rademaker’s Paul Bourke Award for Early Career Research from the Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia and the launch of Everywhen: Australia and the Language of Deep […]

The Cunningham Lecture is the Academy’s flagship annual public lecture. It is named after Dr Kenneth Stewart Cunningham, the first chairman of the Social Science Research Committee (the Academy’s predecessor […]

2022 Keith Hancock Lecture Staggered Starting Blocks: Intergenerational Disadvantage in Australia Presented by Professor Deborah Cobb-Clark Increasing social and economic opportunity is one of the defining challenges of our time. […]

Collective violence against marginalised groups is a tragic phenomenon in many societies. Often such acts are accompanied by specific narratives that justify the necessity for systematic persecution. How do these […]

Given the warnings from scientists of potentially catastrophic changes to our climate from greenhouse gas emissions, it might surprise you to learn that we know very little about the potential […]

Critics often argue in public debate that Indigenous rights conflict with Australian political traditions over the claims of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to land, culture and sovereignty. One […]

2022 Fay Gale Lecture: Presented by Professor Chelsea Watego ‘No room at the Inn’: Rethinking critical race studies and its place in the Australian academy Date: Wed 23 Feb Time: […]

Emotions and Political Change Presented by Dr Emma Hutchison Emotions abound and pervade contemporary local and global politics. From refugees and Indigenous recognition to populism and international conflict, emotions are powerful […]

Public lecture Thursday 3 Dec, 10-11am AEDT

2020 Cunningham Lecture: ‘Do We Need Intellectuals?’ Delivered by Professor Emerita Raewyn Connell FASSA There is a sense of crisis in the university world, produced by the COVID-19 epidemic, the […]

2020 Fay Gale Lecture ‘Delivering Indigenous Data Sovereignty’ Presented by Professor Maggie Walter FASSA The Academy’s 2020 Fay Gale Lecturer Professor Maggie Walter FASSA is a Palawa woman from Lutruwita, […]

Save The Date 2020 Cunningham Lecture Presented by Professor Raewyn Connell FASSA Tuesday 27 October, 12:00 – 1:00pm AEDST The Cunningham Lecture is the Academy’s flagship annual public lecture. It […]

2020 Paul Bourke Award Lecture: On care, welfare conditionality and free riding Care is essential to all life – we need it, we feel it, we desire it and none […]

2020 Paul Bourke Award Lecture: On the Use and History of Monte Carlo Methods In this talk, I give a gentle (non-technical) introduction to the topic of modern (computer-based) Monte […]

2020 Paul Bourke Award Presentation: Press Freedom and National Security Dr Rebecca Ananian-Welsh in Conversation with Professor Peter Greste In 2019, following successive police raids on journalists, Australia dropped 5 […]

2020 Paul Bourke Award Lecture: Non-pharmacological treatments for chronic pain Research has demonstrated that the perception of pain involves a complex network of brain regions associated not only with somatosensory […]

Losing It! Are Australian Governments Still Capable of Exercising the Art of Effective Policy Making? Presented by the Hon. Marcia Neave AO This lecture will identify the elements of the […]

The Pursuit of Knowledge: Veritas Redux Presented by Professor Glenn Withers AO FASSA (Professor ANU and UNSW Canberra) Humans are ascendant because of rational knowledge. In this Lecture the […]

This forum will discuss the insights that can be gained from thinking about politics and policy through a values lens. Our lives are guided by sets of values that underpin our evaluations of good and bad, right and wrong, and what should or should not be.

Patterns of crime in everyday life: Using big data to capture the dynamics of urban social environments The majority of crime events in urban spaces are unplanned and take place […]

Gaming Disorder: Meeting the challenges of a new disorder Digital devices and online media have become integral to young people’s lives, and have enabled new opportunities for socialisation, creativity, and […]

Humans possess the extraordinary capacity to mentally travel back and forth in subjective time. This allows us to relive personally defining events from our past in exquisite detail, and to […]

Two concepts are much bandied about in contemporary public debate about universities: Academic freedom and freedom of speech. Almost everyone agrees that they are very important but opinions differ wildly […]

The high prevalence of mental health problems in Australia continues to place a significant burden on society. To reduce this burden on individuals and communities, new evidence-based approaches to assessment, […]

Since the early 1970s, thousands of white, middle-class, progressive professionals have been moved by the plight of Indigenous communities and sought out work in Indigenous affairs. Emma Kowal became one […]

Experts? Who needs ‘em? – Promoting the Value of Expertise in Decision-Making in Australia’s Future Featuring: Sarah Burr – Senior Adviser, Department of Prime Minister & Cabinet […]

https://youtu.be/IOUsLwJIpuc In this lecture, Associate Professor Rich discusses her research on synaesthesia and the mappings we all have between our senses, giving insights into the way the brain integrates information for conscious […]

Despite the immense processing power of the human brain, severe ‘bottlenecks’ of information processing are revealed when individuals attempt to perform two, even simple, tasks concurrently – that is, multitasking. Under such conditions, performance of one or both tasks is impaired relative to when the tasks are performed in isolation. This performance impairment is exacerbated as humans age and in many psychiatric and neurological conditions. It is thus vital to understand how these multitasking limitations arise and how they can be alleviated. It has previously been shown that multitasking limitations can be drastically reduced with cognitive training. However, the neural basis for these training effects has not been elucidated.

In this lecture Dr. Dux will present behavioural, brain imaging and brain stimulation data which shows that a network of frontal brain regions (including posterior lateral prefrontal cortex, superior medial frontal cortex, and bilateral insula) is associated with capacity limits in perception and decision making. He will also provide evidence that training can reduce multitasking impairments by increasing the processing efficiency of the posterior lateral prefrontal cortex rather than by funneling information away from this bottleneck region.

Update 2013-12-12: Download the presentation slides [PDF 11.7 MB].

Some links to relevant papers from the talk:

http://www.cell.com/neuron/abstract/S0896-6273(06)00903-2

http://www.cell.com/neuron/abstract/S0896-6273(09)00458-9?switch=standard

The Future of Work Presented by Professor John Quiggin The outcomes of technological change are affected by the interaction of changes in the regulation of labour markets and the stance […]

https://youtu.be/7i2qqgwE3HU Over the last three decades, growing international recognition of the right of students with a disability to attend their local school has prompted change in the formation of education […]

Health workforce shortages are commonly described in media and policy discourse as an increasing problem for many ‘advanced liberal’ nations, including Australia. While the structural and economic explanations for this […]

Creating Pathways to Child Wellbeing in Disadvantaged Communities Presented by Prof Ross Homel AO FASSA Children living in economically deprived areas, especially First Nations children, are more likely than those from […]

Humans are characterised by a remarkable ability for flexible thought which enables us to interact in a complex social world. By selecting appropriate thoughts and actions and inhibiting those that […]

Creating pathways to child wellbeing in disadvantaged communities Presented by Professor Ross Homel AO Children living in economically deprived areas, especially First Nations children in these areas, are more likely […]

A Social Science of Failure: why I made mistakes and what I learned from them The diverse disciplines of social science apply their methodologies and pedagogies to understanding human society: […]

The Australian Government, through the Australian Research Council and the Department of Education and Training is assessing how universities are translating their research into economic, social and other benefits and […]

Decolonising Artificial Intelligence? Presented by Professor Genevieve Bell The idea of Artificial Intelligence (AI) was codified at a conference in the American summer of 1956. It was summarised to mean […]

Decolonising Artificial Intelligence? Presented by Professor Genevieve Bell The idea of Artificial Intelligence (AI) was codified at a conference in the American summer of 1956. It was summarised to mean the […]

FEATURING: The Hon Dr Kay Patterson AO When Paul McCartney penned his famous song “Will you still need me…” in 1966, at the age of 16, the oldest of Australia’s baby boomers […]

‘What matters in Social Change?: The uncertain significance of caring’ Presented by Professor Chris Beasley June 2017 Audio recording by Sydney Ideas The intention of this paper is to theorise […]

When US president Theodore Roosevelt was shot in the chest in 1912, he was saved by the luck of having a folded fifty-page speech in his breast pocket. Two years later, World War I was sparked after Franz Ferdinand’s motorcade took a wrong turn onto a narrow street, putting his car into the path of an assassin. John Howard and Gough Whitlam narrowly missed out being elected to state seats – a ‘misfortune’ that left them able to run for safer federal seats.

In this talk, Andrew Leigh will argue that recognising the importance of luck can profoundly alter the way in which all of us think about politics, and about life. Just as a good health system guards against the bad luck of sickness, and a good unemployment system protects against the bad luck of job loss, so too we need a politics that recognises the role of chance. Luck should make us less inclined to revere the successful and revile the unsuccessful. Putting luck into politics may even let the unlucky have a second chance.

The Higher Education Contribution Scheme (HECS) was introduced in Australia over 25 years ago, and was the first nationally-based income contingent loan (ICL) scheme collected through the income tax system. It has since been successfully adopted in eight other countries and a bill is currently before the US Congress which, if passed, will introduce ICL to the US.

The benefits of such instruments have been recognised in research involving several disparate potential applications in financing areas well beyond student loans, including for: extensions of paid parental leave, legal aid, business innovation, health care, drought relief, the payment of low level criminal fines and providing for aged care.

The lecture will examine these applications and explain why the use of ICL is a critical new way of understanding the role of government in an insurance context.

Tobacco control is widely considered the contemporary poster child of successful public health policy and practice in reducing major chronic diseases. In December 2012, the Australian government became the first nation to prescribe the entire packaging for any consumer product when it introduced plain packaging law for tobacco products. The bill attracted sustained opposition from the tobacco industry and its acolytes, a High Court challenge, a World Trade Organisation action and another claimed bilateral trade treaty violation between Australia and Hong Kong. Many millions of dollars were spent unsuccessfully by the tobacco industry in trying to defeat the bill. This lecture will consider both proximal and distal factors in the success of the bill. It will also consider the role of public health advocacy, and specifically the extent to which the case highlights the importance of active engagement by researchers in the policy advocacy process.

Australia’s policy makers are dealing with a mining boom unprecedented in our history. It is a boom that has been much celebrated. But we know that it will not last forever. At present rates of extraction, Australia’s known reserves of iron ore will be exhausted within a human lifetime, and known reserves of black coal will be exhausted within a century. Today, these two products make up more than a third of Australia’s total exports. As a whole, mining contributes about 60 per cent of Australia’s total exports, and at present rates of extraction those exports will last, on average, about 75 years. Of course, there will be further discoveries of mineral deposits in Australia. And rates of extraction could fall as other producers expand capacity and importing countries transform their economies in ways that reduce reliance on raw materials.

Which ever of these scenarios emerges, future generations of Australians will identify the present generation as that which extracted unparalleled monetary reward from the continent’s non-renewable natural resources; a ‘monetisation’ of non-renewable resources unmatched by any previous generation of Australians, and unlikely to be matched by any that follows. Those future generations – our children’s children – will have reason to examine whether we made the most of a mining boom that we knew could not last forever.

Who would want to sit that test?

It’s widely accepted that good policy should be based on a careful analysis of the very best evidence. Australia has a strong record in this regard. But in a ‘post truth’ […]

2015 Peter Karmel Panel Discussion is a Free Public Event, however, booking is essential.

The Peter Karmel Panel Discussion is being organised in conjunction with Committee for Sustainable Retirement Incomes (CSRI), as part of their two day event: Sustainable Retirement Incomes Leadership Forum, on 2nd and 3rd June 2015 at Hyatt Hotel Canberra. (The two day CSRI event is at a charge)

Link to the CSRI Event: CSRI event

Despite two decades of investment in improving mental health services, the mental health of Australians has not improved. This lecture argues that we have used a one-pronged approach to improving […]

Public policy can be hard, both technically (what to do?) and politically (how to get it done?). Australian governments have often made use of public inquiries or reviews to assist […]

Economic Modelling now plays a significant role in the development of public policy development and the conduct of public debate in Australia. Modelling has been central to the case for […]

Behind every policy strategy, of government or business, lies a narrative that contextualises and justifies a course of action. Restrictive immigration policies are necessary to prevent an oversupply of labour and a taxing of our natural resources… allegedly. Who develops these narratives and how well informed are they? Often they derive from the thinking of influential foreign and supranational organisations, or the conventional wisdom and philosophies of domestic political parties and powerful media organisations. In this lecture, Simon Ville argues that the design of narratives that best shape our future must draw deeply upon our national historical experience.

The newly-published Cambridge Economic History of Australia provides a modern statement of our past experience to guide our economic narratives for the Asian century, highlighting our sources of resilience and exposing our potential frailties.

The Academy in conjunction with UNSW and CEPAR, is pleased to present the 2013 Keith Hancock Lecture by Scientia Professor John Piggott, a Fellow of the Academy of the Social […]

Economics is unique among the social sciences in having a single monolithic mainstream, which is either unaware of or actively hostile to alternative approaches.

In this lecture Professor John King of La Trobe University will present a case for pluralism in economics, derived from the complex and ceaselessly changing nature of the world in which we live. Professor King argues that ‘Economics is unique among the social sciences in having a single monolithic mainstream, which is either unaware of or actively hostile to alternative approaches.’

https://youtu.be/eK79Nk4gAlU Compared to any other region in the world, South East Asia has the largest volume of irregular border crossings, what many refer to as ‘illegal’ migration. Border crossings have become […]

What are the social sciences? What do they do? How are they practised in Australia? This lecture considers the place of the social sciences in the teaching and research conducted […]

A comparative perspective Wage inequality has been increasing in most industrialized countries over the last three decades. There are, nonetheless, major differences across countries in terms of the timing and […]

What are the consequences of the most significant change in the Australian labour market in the past three decades?– the growth in women’s participation. What has this change – alongside the decline in men’s participation – meant for society, the economy, households and gender equality? Why are jobs still made largely in men’s image, while responsibility for the household and care remains largely with women? We have witnessed an incomplete revolution in our lifetimes, where the public world has simultaneously hungered for women’s time, while resisting renovation of the institutions that meet them at work and at home. What needs to be done for future fairness, especially in the context of an ageing population? Having lived through this incomplete revolution herself, and participated in many of the major policy debates of the past three decades, in this lecture Barbara Pocock reflects on where we are at, what working men and women need now, and how we might get there.

International relations scholars as well as psychologists have recently claimed that violence – defined largely as homicide and casualties from war – is in steep decline. On these accounts, human beings are becoming more civilized. However, research dedicated to making the case for decline with reference to historical and quantitative data has almost completely neglected evidence of gendered violence. Sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) has been largely invisible, silent and unreported yet prevalence surveys reveal that the majority of women and girls in every country, that is, a large proportion of the total world population, have experienced this form of violence. According to the cross-national International Violence against Women survey (IVAWS) the number of women who have experienced at least one incident of physical or sexual violence since age sixteen is between 20 and 60 per cent with an average victimization rate of over 35 per cent. Moreover, declinist perspectives on violence and war seem to go against contemporary reporting of widespread and systematic SGBV especially targeting civilians in genocide, conflict and mass atrocity situations. Violence against women and girls (VAWG) has been the subject of nearly four decades of feminist scholarship, activism and policy interventions. Analysing global violence from a feminist perspective on VAWG radically challenges declinist views and our understanding of the causes, justifications, and consequences of violence.

The lecture will explore whether policy-makers are responding sufficiently to the evidence of the food system’s tensions and fragilities. Tim Lang will propose that a set of ‘New Fundamentals’ are now clear yet policy-makers have so far failed to get sufficient intellectual, political and economic grip on the seriousness of the situation. For a moment, in 2006-08, this looked possible. Rising oil and food commodity prices shocked even Western policy-makers. They were used to food prices troubling developing, but not developed, countries. When prices dropped, sighs of relief were heard, but troubles have re-emerged in the 2010s. Are the tectonic plates merely moving only to resettle in a new place, or is food economic volatility now the status quo, adding to the world’s financial instability?

In this lecture, Tim Lang will take a long view. He will suggest that the 20th century’s apparent progress in resolving the Malthusian question (about land, food and population) has been done at considerable cost. Oil underpinned the 20th century drive for productivity. As it went through technical and managerial revolutions, the food system’s impact on the environment was increasingly well documented. The impact on soil, water, climate, land use, and biodiversity are now all serious. The social implications, too, are sobering. Food culture is distorted. Social inequalities in consumption are both global and intra-national. Health indices show both hunger and obesity; and diet-related disease delivers huge healthcare costs. Surely the prevention of such problems ought to be driving policy yet it does not. Surely, we ought to be debating resource allocation, price-setting, and what is meant by efficiency, yet business-as-usual reigns. Or does it?

The lecture will present some signs that the enormity of the challenge is troubling policy-makers’ normality. The lecture will suggest that governments, food companies, and civil society (ie all of us) need to engage with this debate. It should not be left to vested interests alone. Thus, the 21st century looks set to resuscitate an old strand in food policy: the pursuit of food democracy, how to ensure that all people are fed equitably, healthily and with dignity in a manner that enables others to do so too. This is a socio-political not a purely technical or managerial or scientific problem.

Currently, much attention is on technical innovation – not just GM but an array of novel solutions to food on and off the land. Less attention is being given to social issues where the possibilities include: restructuring food markets, rapid consumer behaviour change, re-shaping cultural tastes, altering price signals. These require the state and citizens to act differently: less ‘leave it to markets’ and more ‘re-frame markets’. Less ‘let consumers choose’, more open support for ‘consumers are choice-edited anyway’. The dominant policy language is, at best, replete with ‘nudge’ thinking, the fashion for behavioural economics. The lecture will propose the need for open and democratic debate about food futures. It will propose that the food security debates are no more and no less than a key test for whether our food system is shaped by food control or food democracy. It will warn against technical triumphalism and urge a more balanced integration of societal and supply chain change.

In the last decade liberal arts colleges have sprung up across Asia. What accounts for this sudden interest in the liberal arts? What aspirations do they serve? What models are […]

The 2011 Fay Gale Lecture was presented by Associate Professor Denise Doiron on the theme ‘Trends and recent developments in income inequality in Australia’. The lecture was presented first at Associate Professor Doiron’s home university, the University of New South Wales, on 20 September 2011, and then at the University of Western Australia on 26 October 2011. The final lecture was at the University of Tasmania in Hobart on 23 November 2011. The lecture was jointly sponsored by ASSA, the Economics Society of Australia (Tasmanian Branch) and the University of Tasmania.

In 1972, the late Fay Gale (AO) published a characteristically self-styled book titled Urban Aborigines. It launched a richly diverse career that delivered an exceptional legacy to the academic discipline of geography, Aboriginal justice, university administration, and women’s professional advancement.

This lecture honours Fay’s intellectual contribution to one of these fields. It pursues her critical interest in the clash of indigenous/settler cultures in Australia through a fresh account of the notorious head-measuring practices of 19th century racial craniometry.

Probing the Western premise that ‘mind’ is the assured marker of human distinction from nature, the lecture asks: are there fresh prospects for reconciling settler and indigenous values on this continent if the conceit of this distinction can be overcome? This fundamental question for the Anthropocene is provoked from a ‘southern’ perspective in the sprit of the insistently geographic project that was Urban Aborigines.

The integrated wisdom of mainstream science and mainstream economics identify large risks to established patterns of human civilisation from unmitigated or weakly mitigated climate change. These risks are important in all countries, and greater in Australia than in any other developed country. They have been more elaborately analysed in Australia than in most other countries, and our community has had access to large amounts of reliable information on the risks. And yet Australia has been and is an important brake on international progress on mitigation policy. There is political failure of fateful dimension. This lecture defines the failure and seeks to illuminate the causes of this unhappy reality. It suggests possible ways out of the impasse, and discusses factors which will determine whether these ways will be taken.

The contemporary prominence of climate change confirms the democratic and ecological deficits of global governance. When authority migrates from states into the international system, democracy does not usually follow, causing problems in a world where legitimate political authority ought to be democratic. There is no World Environment Organisation to match (say) the World Trade Organisation. The two deficits may be linked, for in national contexts democratic innovation and environmental concern have often proved mutually reinforcing. The democratisation of global environmental governance can be approached by contemplating how the engagement of discourses in the global public sphere can be subject to more inclusive and competent control. Then we might think about how this engagement could join in a more deliberative system in which effective authority is exercised. The results are likely to look very different from familiar state-based electoral democracy.

It has been a commonplace since the end of the Cold War to refer to the United States as the world’s only super-power. What nonsense this is – and what illusions it fosters! In the currency of effective military power for today’s wars, particularly well trained infantry, marines and their supporting arms on the ground, the United States is simply a major power, contending with many other powers major and minor – some even at subnational level – who can outmanoeuvre and outlast the American will. The United States does not have the necessary military superiority in a major regional war to ensure victory. It is at full stretch militarily, economically, socially and politically with the current conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. Not even George W Bush is willing to re-introduce the draft. The United States is the strongest power in the world overall, but it has shortcomings in the particular field in which it has chosen to engage militarily.

Experience of the past four years calls into question the widely proclaimed official view that the United States will eventually emerge victorious from Iraq and Afghanistan. Rather, I suggest, we should give some consideration to what will happen to American leadership and prestige if the US is defeated in either place. There will be some major consequences. Let me briefly offer four case studies in the problems of remaining Number One in a turbulent world.

It is a great honour to be asked to deliver this lecture, named for the educationist, Dr Kenneth Cunningham, the first President of the Social Science Research Council, which became this Academy. After retiring, he worked with UNESCO on teacher education, so I hope he would have some interest in my topic.

It has been said that democracy or state-building has ‘become one of the critical all-consuming strategic and moral imperatives of our terrorised time’. But open any newspaper, listen to the radio or watch the TV news: all around us is evidence of the problems flowing from attempts to build democracy and justice after conflict.

It is a great privilege to deliver this year’s Cunningham Lecture to the Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia, on a subject more challenging than ever: the dynamics within our system of governance. As I wrote this Lecture I reflected that it is 30 years ago this week that we witnessed the Dismissal – the product of personality conflict and defects within our system. Yet at that same time in the early 1970s we saw the birth of another phenomenon that has run unbroken for more than three decades, ubiquitous and elusive, the rise of Prime Ministerial Government. Its face has changed from Gough Whitlam to John Howard – but Prime Ministerial Government is the central organising principle of our current system.

Is this a good or bad trend for Australia’s democracy and governance? Opinions will differ – last year Justice Michael Kirby said: "Governance and good governance have attracted many definitions. But the notion remains a ‘contested concept’". The Howard era has provoked an escalation in the debate about what constitutes good governance, a debate riddled with differences over perspective and public interest. They are unlikely to be reconciled.

In this Cunningham Lecture my goal is to describe how Australian Governance is being re-shaped and re-thought by John Howard. The reason I chose this approach is that while there is a multitude of commentary about Howard’s governance, there is little analysis of how he governs or of the ideas and approach that shape his governance or of what might become his legacy.

It is an honour to have been asked to deliver the 2004 Cunningham Lecture. I know people always say that sort of thing; but on this occasion I say it not just in deference to the conventions of politeness (which I may later violate anyway) but also with a certain ‘special intellectual intent’. Because honour, glory, fame, regard, approval – and their corresponding opposites – dishonour, contempt, shame, disregard, disapproval – constitute the theme of this lecture. My interest in this family of phenomena is not just as objects of social analysis in their own right, but more especially in the normative possibilities they offer – their possible role as a resource in institutional design.

I shall generally use the term ‘esteem’ to stand for the whole family. I don’t deny that there are distinctions to be drawn between, say, esteem and approval, or between esteem and fame. But I also don’t want here to engage in fine-grained logic-chopping – so I hope that I will be forgiven if I suspend a lot of relevant distinctions in the interests of painting on a slightly larger canvas.

The subject of leadership can be approached in many different ways. How we approach leadership – who and what we choose to study, the activities and events we attempt to analyse, and the conceptual frameworks we use to understand leadership – determines what we see and therefore what is concluded. Who is a leader? How important are leaders? What difference do they make? What drives and motivates them? What makes a capable leader? What is the essence of effective leadership? How do we nurture leadership?

In a 1998 review of leadership theory and research it was observed that ‘most of the research on leadership during the past half century has been conducted in the United States, Canada and Western Europe.’ In addition, it has been noted that ‘almost all of the prevailing theories of leadership and about 98 per cent of the empirical evidence at hand, are distinctly American in character: individualistic rather than collectivistic, stressing follower responsibilities rather than rights…’. But in many Asian countries there is a long tradition of writing about political, military, and spiritual leadership as well as a strong research interest in the moral dimension of leadership. Rost, who conducted a historical review of the literature on leadership, concluded ‘leadership… has come to mean many things to all people’ and that ‘scholars and practitioners of leadership are no more sure of what leadership is in 1990 than they were in 1930’. While the diversity of views about leadership may indicate a field without direction, a more positive reading is that there are many valid ways to define, approach, and understand leadership and this testifies both to the complexity and the richness of the field.

Much of the data in this article comes from a paper commissioned by the Australian Bureau of Statistics for the Millenium Year Book, entitled Child Health since Federation. This enabled me to compare the statistics on childhood deaths and diseases and investigate their trends over the last 100 years, and I believe that from this a clear message emerges for us now in the 21st century. The epidemics of infections which killed so many infants around 1900 were contained by a series of community based, social and physical environmental strategies. In spite of inadequate knowledge about the responsible organisms and without access to either antibiotics or vaccines, they were remarkably successful.

As we start a new century, in spite of the increases in wealth, and educational and technological advances compared with 100 years ago, we are challenged by alarming increases in childhood and adolescent problems in physical and mental health. Many arise in social adversity and have coincided with recent profound social changes in society.

One use of a lecture in such intelligent company would be to sketch a social democratic future in which Australians become even richer, freer, more equal, more cooperative, fonder of one another and happier than most of us already are.

I could do that, but I know what the realists among you

The year 2000 not only marked the millennium in Western calendars but, as a sign of millennial optimism perhaps, was declared by the United Nations to be the International Year for a Culture of Peace, inaugurating an International Decade for Peace. UNESCO was selected as the focal UN agency for all related activities. In response to an approach from UNESCO Australia, both the Academy of Social Sciences and the Academy of Humanities focused their annual symposia on the question of peace. The ASSA Symposium on 5 November 2000 was organised under the rubric of ‘thinking peace, making peace’. Our aim was to combine the insights of scholars and practitioners – to connect the intellectual challenges of ‘thinking peace’ with the moral and political challenges of ‘making peace’ – in a world pervaded by violence and war.

The most persistent imagery in literature, particularly in poetry, is human frailty, especially the inevitability of death. ‘Mortals’ is a term used to designate the human race. Demography, which focuses on the major events of our existence – birth, marriage, parenthood and death – has long been interested in measuring the force of mortality and in explaining its change.

This preoccupation is not as morbid as it sounds. In modern times the news has been almost entirely good. Western countries have doubled their life expectancies from around 40 years in the mid-nineteenth century to almost 80 years at the end of the twentieth century. The Third World’s life expectancy, taken as a whole, has climbed from 40 years in the mid-twentieth century to 65 years at its end3. If we were to enter one of those competitions to nominate the greatest advance of the latter part of the millennium, it would be difficult to overlook the pushing back of the frontiers of death and the guarantee that most people will live to old age. In Sweden, for which we have good statistics for the last two centuries, the 1800 mortality level would have meant only one-third of those born surviving until 60 years of age. In contrast, the present mortality level implies that such erosion does not take place until after 85 years.

It is with considerable trepidation that I give this lecture. The topic is not just complex and immense, but it has been so taken over by the media and so politicised by so many varying and vested interests, that any objective discussion that satisfies everyone will be impossible. In the light of this, I decided to present a personal view based on past study and fieldwork.

I have been rather nervous about giving this lecture knowing that many reading would be better versed in the complexities of the issues than I am. But in preparing it I remembered the Academy symposium of 1981 when, as a relatively new Fellow, I chaired a session on Aboriginal land rights. What I remember most was sitting on the platform between Charles Perkins on one side and Hugh Morgan on the other and trying to keep some focus and calm discussion. So let me begin.